by Victor R. Volkman, Senior Editor, Modern History Press

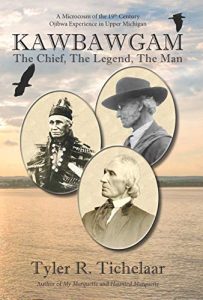

TITLE: Kawbagam: The Chief, The Legend, The Man

AUTHOR: Tyler R. Tichelaar

PUB DATE: Nov. 2020

PUBLISHER: Marquette Fiction.

Kawbawgam by Tyler R. Tichelaar, PhD, is the first woke history of Native Americans in Upper Michigan that I have read. I’ll go so far as to presume that it was awakening for the author as well, despite or because of having been a 7th generation resident of Marquette, Michigan’s Queen City of the North. He confesses to having grown up with the myth of Ojibwa tribesmen welcoming the landing of white men in what would become that city and essentially handing them the keys to a vast mineral and timber wealth without a second thought. Indeed, a reenactment of this event has happened in recent history as the city celebrates its Founders Day. It’s not an absurd notion at all, considering there was no significant Indian-on-white warfare or hostilities in the central U.P. However, as a culture that didn’t believe you could own the land any more than you can own the sky, it was the beginning of a downward slide that would span the better part of two centuries.

Kawbawgam by Tyler R. Tichelaar, PhD, is the first woke history of Native Americans in Upper Michigan that I have read. I’ll go so far as to presume that it was awakening for the author as well, despite or because of having been a 7th generation resident of Marquette, Michigan’s Queen City of the North. He confesses to having grown up with the myth of Ojibwa tribesmen welcoming the landing of white men in what would become that city and essentially handing them the keys to a vast mineral and timber wealth without a second thought. Indeed, a reenactment of this event has happened in recent history as the city celebrates its Founders Day. It’s not an absurd notion at all, considering there was no significant Indian-on-white warfare or hostilities in the central U.P. However, as a culture that didn’t believe you could own the land any more than you can own the sky, it was the beginning of a downward slide that would span the better part of two centuries.

For myself, I grew up with an equally biased but opposite view of Native American culture in Michigan. Having all of my mom’s family living in Mackinaw City, we visited the fort there as archaeologists were uncovering mysteries in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Positioned under the base of the Mackinac Bridge, which is of course the closest juncture between the two peninsulas, it has broad panoramic views and the recreated wooden fortress was enchanting to visit as a small boy. And so I was weaned on Attack at Michimilimackinac – 1763, the grossly abridged edition of Alexander Henry’s two-volume memoir Travels & Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories between the years 1760 and 1776. In it, it describes the cold-blooded plot to wholesale murder an entire garrison of American soldiers by luring them outside the protective walls to be spectators at a game of lacrosse. I’m sure it cemented my fear of the Other, growing up as I did in one of the most privileged white suburbs of Detroit.

At any rate, there is plenty of history to reconcile and atone for as a white citizen of Michigan. Kawbawgam: The Chief, The Legend, The Man is a great start for anyone willing to confront the true history of the colonization of the U.P. and the ruthless exploitation of its indigenous peoples. This is not Tichelaar’s first outing into U.P. history; he is broadly recognized for writing accessible histories such as “My Marquette” and “When Teddy Came to Town” as well as the sprawling Marquette Trilogy, a Micheneresque rendition of 150 years in historical fiction. The Kawbawgam book uses the chief’s extended family as a lens to view the span of history from about 1815 to 1905. Indeed, unraveling the birth and age of Kawbawgam is one of the central mysteries of the book and is approached from several angles. As an adult he was on hand for the famous landing of settlers in Marquette and by his old age his image was being exploited as a tourist curiosity in his role as the putative “last full-blooded Indian Chief of his tribe” and a model of a “good Indian.”

Tyler R. Tichelaar

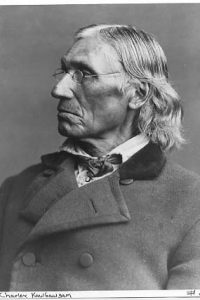

Tichelaar easily debunks the full-blooded claim as it was widely known even then that Kawbawgam’s mother was of Scottish descent. Indeed, the French-Canadians had been widely intermarried with the Ojibwe at Sault Ste. Marie (some 136 mles east of Marquette) for generations. Other myths the author tackles include the false notion that Kawbawgam lived to the ripe old age of 102 in robust health. The truth painful to watch as Kawbawgam descends from beloved chief of the local tribe to being exiled to an Indian settlement north of town and finally to a city park where Peter White takes pity on him and builds him a frame house. The final public scene of Kawbawgam’s life is filled with a cruel irony, when he is hauled out to a picnic for visiting reporters where he sits in isolation, completely blind at this point and having never become fluent in English, he sits stony-still like a man who has become a statue and merely the icon of living flesh. By Tichelaar’s account he died probably around the age of 86.

Central to the story portrayed is the relationship of Marquette pioneer Peter White to Kawbawgam. White was apprenticed to a storekeeper at Mackinac Island as a teenager and quickly became a master of the Ojibwa language. As such, he was much in demand as a scout and it was almost inevitable that he would join the expeditions through Lake Superior and into the interior of the U.P. As White grew in stature, he became a shrewd real estate investor, businessman, and increasingly the liaison between white people and the Ojibwa in general and to Kawbawgam in particular. White wasn’t the first white man to fetishize the “full-blooded Indians” myth and add decades of age to portray extreme longevity. Tichelaar nails this precisely by labeling it “imperial nostalgia.”

It is the cutting through this smoky haze of imperial nostalgia that Tichelaar does yeoman work, going back to original sources where most contemporaries have simply regurgitated newspaper reporting of prior decades and the embellished yarns of Peter White’s well-meaning if hopelessly biased accounts. The sources fully documented and footnoted include census records, church baptism, marriage, and death records, original court documents, as well as letters and contemporaneous newspaper reporting. Tichelaar concedes that this work won’t be the last word on Kawbawgam and instead hopes that it will perhaps revive scholarship and bring new sources to light. His 3+ years of meticulous research and fact-checking bring authority to the work.

There’s much more to Kawbawgam’s story than I can possibly relate here, from his role in helping deliver mail hundreds of miles by snowshoe to his family’s role in the “discovery” of iron ore near Marquette and its exploitation. Kawbawgam was also involved in the several disastrous treaties that culminated in the total loss of all land rights in the U.P. save a few reservations in the west. Living under the constant threat of his entire tribe’s removal to Minnesota, capitulation and appeasement were the only practical options for the Ojibwe. The book also covers in some detail the removal of tribes from the Soo and how its eponymous locks both enabled the export of iron ore and destroyed a tribe including its sacred burial grounds. This is just a small taste of Tichelaar’s treatise on Kawbawgam and I believe that anyone with even a casual interest in how the U.P. got to be the way that it is in 2020 can take the time to explore the journey of a man who bore witness to its formative years in white history.

Kudos to Mr. Tichelarr for a detailed, accurate book. Looking forward to reading it.